Painter Artist Begins the Transition From Realism to Impressionism in the Art World

| Édouard Manet | |

|---|---|

Édouard Manet before 1870 | |

| Born | (1832-01-23)23 January 1832 6th arrondissement of Paris, France |

| Died | 30 Apr 1883(1883-04-30) (aged 51) 8th arrondissement of Paris, France |

| Resting place | Passy Cemetery, Paris |

| Pedagogy | Collège-lycée Jacques-Decour, Académie Suisse |

| Known for | Painting, printmaking |

| Notable work |

|

| Motion | Realism, Impressionism |

| Spouse(due south) | Suzanne Leenhoff (k. 1863) |

Édouard Manet (, ;[1] [2] French: [edwaʁ manɛ]; 23 January 1832 – 30 April 1883) was a French modernist painter. He was one of the first 19th-century artists to paint modern life, as well as a pivotal figure in the transition from Realism to Impressionism.

Born into an upper-class household with strong political connections, Manet rejected the naval career originally envisioned for him; he became engrossed in the world of painting. His early masterworks, The Luncheon on the Grass (Le déjeuner sur 50'herbe) and Olympia, both 1863, acquired bully controversy and served as rallying points for the young painters who would create Impressionism. Today, these are considered watershed paintings that mark the start of modernistic art. The last 20 years of Manet'south life saw him grade bonds with other great artists of the time; he adult his own elementary and direct manner that would exist heralded as innovative and serve as a major influence for future painters.

Early life [edit]

Édouard Manet was born in Paris on 23 January 1832, in the ancestral hôtel particulier (mansion) on the Rue des Petits Augustins (now Rue Bonaparte) to an affluent and well-connected family.[3] His female parent, Eugénie-Desirée Fournier, was the girl of a diplomat and goddaughter of the Swedish crown prince Charles Bernadotte, from whom the Swedish monarchs are descended. His begetter, Auguste Manet, was a French estimate who expected Édouard to pursue a career in police. His uncle, Edmond Fournier, encouraged him to pursue painting and took immature Manet to the Louvre.[4] In 1841 he enrolled at secondary school, the Collège Rollin. In 1845, at the advice of his uncle, Manet enrolled in a special course of drawing where he met Antonin Proust, future Government minister of Fine Arts and subsequent lifelong friend.

At his father's suggestion, in 1848 he sailed on a training vessel to Rio de Janeiro. Later he twice failed the examination to bring together the Navy,[five] his father relented to his wishes to pursue an art education. From 1850 to 1856, Manet studied under the academic painter Thomas Couture. In his spare time, Manet copied the Former Masters in the Louvre.

From 1853 to 1856, Manet visited Federal republic of germany, Italy, and the netherlands, during which time he was influenced by the Dutch painter Frans Hals and the Spanish artists Diego Velázquez and Francisco José de Goya.

Career [edit]

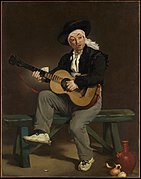

In 1856, Manet opened a studio. His style in this flow was characterized by loose brush strokes, simplification of details, and the suppression of transitional tones. Adopting the electric current style of realism initiated by Gustave Courbet, he painted The Absinthe Drinker (1858–59) and other contemporary subjects such as beggars, singers, Gypsies, people in cafés, and bullfights. After his early career, he rarely painted religious, mythological, or historical subjects; religious paintings from 1864 include his Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers,[6] in the Art Establish of Chicago, and The Dead Christ with Angels,[7] in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Manet had two canvases accepted at the Salon in 1861. A portrait of his mother and father, who at the time was paralysed and robbed of oral communication past a stroke, was ill-received past critics. The other, The Spanish Singer, was admired by Théophile Gautier, and placed in a more conspicuous location every bit a result of its popularity with Salon-goers. Manet's work, which appeared "slightly slapdash" when compared with the meticulous style of so many other Salon paintings, intrigued some young artists. The Castilian Singer, painted in a "foreign new fashion[,] acquired many painters' eyes to open and their jaws to drop."[a]

Music in the Tuileries [edit]

Music in the Tuileries is an early example of Manet's painterly style. Inspired by Hals and Velázquez, it is a harbinger of his lifelong involvement in the subject of leisure.

While the motion picture was regarded as unfinished past some,[4] the suggested atmosphere imparts a sense of what the Tuileries gardens were like at the fourth dimension; ane may imagine the music and conversation.

Here, Manet has depicted his friends, artists, authors, and musicians who take part, and he has included a self-portrait amid the subjects.

Tiffin on the Grass (Le déjeuner sur l'herbe) [edit]

A major early piece of work is The Lunch on the Grass (Le Déjeuner sur fifty'herbe), originally Le Bain. The Paris Salon rejected it for exhibition in 1863, only Manet agreed to showroom it at the Salon des Refusés (Salon of the Rejected) which was a parallel exhibition to the official Salon, every bit an alternative exhibition in the Palais des Champs-Elysée. The Salon des Refusés was initiated by Emperor Napoleon Three as a solution to a problematic situation which came almost every bit the Choice Committee of the Salon that twelvemonth rejected 2,783 paintings of the c. 5000. Each painter could determine whether to take the opportunity to showroom at the Salon des Refusés, although fewer than 500 of the rejected painters chose to exercise so.

Manet employed model Victorine Meurent, his wife Suzanne, futurity brother-in-police Ferdinand Leenhoff, and one of his brothers to pose. Meurent also posed for several more of Manet'southward important paintings including Olympia; and by the mid-1870s she became an accomplished painter in her ain right.

The painting'south juxtaposition of fully dressed men and a nude woman was controversial, every bit was its abbreviated, sketch-like handling, an innovation that distinguished Manet from Courbet. At the same fourth dimension, Manet'due south composition reveals his study of the old masters, every bit the disposition of the main figures is derived from Marcantonio Raimondi'due south engraving of the Judgement of Paris (c. 1515) based on a drawing by Raphael.[4]

Ii additional works cited past scholars every bit important precedents for Le déjeuner sur l'herbe are Pastoral Concert (c. 1510, The Louvre) and The Tempest (Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice), both of which are attributed variously to Italian Renaissance masters Giorgione or Titian.[9] The Tempest is an enigmatic painting featuring a fully dressed man and a nude adult female in a rural setting. The human being is standing to the left and gazing to the side, apparently at the woman, who is seated and breastfeeding a baby; the relationship between the ii figures is unclear.[10] In Pastoral Concert, 2 clothed men and a nude woman are seated on the grass, engaged in music making, while a 2nd nude adult female stands beside them.

Olympia [edit]

Equally he had in Luncheon on the Grass, Manet again paraphrased a respected work by a Renaissance artist in the painting Olympia (1863), a nude portrayed in a style reminiscent of early studio photographs, merely whose pose was based on Titian'southward Venus of Urbino (1538). The painting is likewise reminiscent of Francisco Goya's painting The Nude Maja (1800).

Manet embarked on the canvass after being challenged to give the Salon a nude painting to display. His uniquely frank delineation of a cocky-assured prostitute was accepted by the Paris Salon in 1865, where it created a scandal. According to Antonin Proust, "only the precautions taken past the administration prevented the painting existence punctured and torn" past offended viewers.[11] The painting was controversial partly because the nude is wearing some small items of wearable such as an orchid in her hair, a bracelet, a ribbon effectually her neck, and mule slippers, all of which accentuated her nakedness, sexuality, and comfortable courtesan lifestyle. The orchid, upswept hair, black cat, and bouquet of flowers were all recognized symbols of sexuality at the time. This modern Venus' body is thin, counter to prevailing standards; the painting'south lack of idealism rankled viewers. The painting's flatness, inspired by Japanese wood cake art, serves to make the nude more human and less voluptuous. A fully dressed black servant is featured, exploiting the and then-current theory that black people were hyper-sexed.[four] That she is wearing the article of clothing of a servant to a courtesan here furthers the sexual tension of the piece.

Olympia's torso too equally her gaze is unabashedly confrontational. She defiantly looks out as her servant offers flowers from 1 of her male suitors. Although her mitt rests on her leg, hiding her pubic expanse, the reference to traditional female person virtue is ironic; a notion of modesty is notoriously absent in this piece of work. A contemporary critic denounced Olympia'southward "shamelessly flexed" left mitt, which seemed to him a mockery of the relaxed, shielding manus of Titian'due south Venus.[12] Likewise, the alarm black true cat at the foot of the bed strikes a sexually rebellious note in contrast to that of the sleeping domestic dog in Titian's portrayal of the goddess in his Venus of Urbino.

Olympia was the subject area of caricatures in the pop press, merely was championed past the French advanced community, and the painting'due south significance was appreciated past artists such equally Gustave Courbet, Paul Cézanne, Claude Monet, and later Paul Gauguin.

Every bit with Luncheon on the Grass, the painting raised the upshot of prostitution within contemporary French republic and the roles of women within society.[4]

Life and times [edit]

After the decease of his father in 1862, Manet married Suzanne Leenhoff in 1863. Leenhoff was a Dutch-born pianoforte teacher 2 years Manet's senior with whom he had been romantically involved for approximately ten years. Leenhoff initially had been employed by Manet's father, Auguste, to teach Manet and his younger brother piano. She also may have been Auguste's mistress. In 1852, Leenhoff gave nascency, out of marriage, to a son, Leon Koella Leenhoff.

Manet painted his married woman in The Reading, amongst other paintings. Her son, Leon Leenhoff, whose father may have been either of the Manets, posed often for Manet. Most famously, he is the subject of the Boy Carrying a Sword of 1861 (Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, New York). He also appears as the male child conveying a tray in the background of The Balcony (1868–69).[13]

Manet became friends with the Impressionists Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Paul Cézanne, and Camille Pissarro through another painter, Berthe Morisot, who was a member of the group and drew him into their activities. They later became widely known as the Batignolles group (Le groupe des Batignolles).

The supposed k-niece of the painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Morisot had her beginning painting accustomed in the Salon de Paris in 1864, and she connected to evidence in the salon for the next ten years.

Manet became the friend and colleague of Morisot in 1868. She is credited with convincing Manet to try plein air painting, which she had been practicing since she was introduced to information technology by another friend of hers, Camille Corot. They had a reciprocating relationship and Manet incorporated some of her techniques into his paintings. In 1874, she became his sister-in-law when she married his brother, Eugène.

Unlike the core Impressionist group, Manet maintained that modern artists should seek to showroom at the Paris Salon rather than abandon it in favor of independent exhibitions. Nonetheless, when Manet was excluded from the International Exhibition of 1867, he set up his own exhibition. His mother worried that he would waste all his inheritance on this project, which was enormously expensive. While the exhibition earned poor reviews from the major critics, it too provided his commencement contacts with several future Impressionist painters, including Degas.

Although his own work influenced and anticipated the Impressionist style, Manet resisted involvement in Impressionist exhibitions, partly because he did non wish to be seen as the representative of a group identity, and partly because he preferred to exhibit at the Salon. Eva Gonzalès, a girl of the novelist Emmanuel Gonzalès, was his merely formal student.

He was influenced by the Impressionists, especially Monet and Morisot. Their influence is seen in Manet's use of lighter colors: later on the early 1870s he fabricated less employ of dark backgrounds only retained his distinctive utilize of blackness, uncharacteristic of Impressionist painting. He painted many outdoor (plein air) pieces, only always returned to what he considered the serious work of the studio.

Manet enjoyed a shut friendship with composer Emmanuel Chabrier, painting two portraits of him; the musician owned 14 of Manet's paintings and dedicated his Impromptu to Manet's wife.[fourteen]

Ane of Manet'south frequent models at the showtime of the 1880s was the "semimondaine" Méry Laurent, who posed for seven portraits in pastel.[15] Laurent'south salons hosted many French (and even American) writers and painters of her fourth dimension; Manet had connections and influence through such events.

Throughout his life, although resisted by fine art critics, Manet could number equally his champions Émile Zola, who supported him publicly in the press, Stéphane Mallarmé, and Charles Baudelaire, who challenged him to depict life equally it was. Manet, in plough, drew or painted each of them.

Café scenes [edit]

The Café-Concert, 1878. Scene set up in the Cabaret de Reichshoffen on the Boulevard Rochechouart, where women on the fringes of society freely intermingled with well-heeled gentlemen.[16] The Walters Art Museum.

Manet's paintings of café scenes are observations of social life in 19th-century Paris. People are depicted drinking beer, listening to music, flirting, reading, or waiting. Many of these paintings were based on sketches executed on the spot. Manet often visited the Brasserie Reichshoffen on boulevard de Rochechourt, upon which he based At the Cafe in 1878. Several people are at the bar, and one adult female confronts the viewer while others wait to be served. Such depictions represent the painted journal of a flâneur. These are painted in a manner which is loose, referencing Hals and Velázquez, yet they capture the mood and feeling of Parisian night life. They are painted snapshots of bohemianism, urban working people, as well as some of the bourgeoisie.

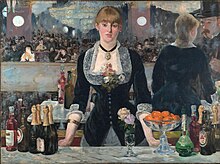

In Corner of a Café-Concert, a human smokes while behind him a waitress serves drinks. In The Beer Drinkers a woman enjoys her beer in the visitor of a friend. In The Café-Concert, shown at right, a sophisticated admirer sits at a bar while a waitress stands resolutely in the background, sipping her drink. In The Waitress, a serving woman pauses for a moment behind a seated customer smoking a pipe, while a ballet dancer, with artillery extended as she is about to plow, is on phase in the groundwork.

Manet also sat at the restaurant on the Artery de Clichy called Pere Lathuille's, which had a garden in addition to the dining area. One of the paintings he produced here was Chez le père Lathuille (At Pere Lathuille's), in which a man displays an unrequited interest in a woman dining near him.

In Le Bon Bock (1873), a large, cheerful, bearded man sits with a pipe in 1 hand and a glass of beer in the other, looking straight at the viewer.

[edit]

Manet painted the upper class enjoying more formal social activities. In Masked Ball at the Opera, Manet shows a lively crowd of people enjoying a party. Men stand up with top hats and long blackness suits while talking to women with masks and costumes. He included portraits of his friends in this pic.

His 1868 painting The Dejeuner was posed in the dining room of the Manet house.

Manet depicted other popular activities in his work. In The Races at Longchamp, an unusual perspective is employed to underscore the furious energy of racehorses equally they rush toward the viewer. In Skating, Manet shows a well dressed woman in the foreground, while others skate backside her. Ever in that location is the sense of agile urban life continuing behind the subject, extending outside the frame of the canvas.

In View of the International Exhibition, soldiers relax, seated and standing, prosperous couples are talking. At that place is a gardener, a boy with a dog, a woman on horseback—in curt, a sample of the classes and ages of the people of Paris.

State of war [edit]

Manet's response to modern life included works devoted to war, in subjects that may exist seen as updated interpretations of the genre of "history painting".[17] The first such work was The Battle of the Kearsarge and the Alabama (1864), a body of water skirmish known every bit the Battle of Cherbourg from the American Civil War which took identify off the French coast, and may have been witnessed past the artist.[eighteen]

Of interest side by side was the French intervention in Mexico; from 1867 to 1869 Manet painted iii versions of the Execution of Emperor Maximilian, an event which raised concerns regarding French foreign and domestic policy.[xix] The several versions of the Execution are among Manet's largest paintings, which suggests that the theme was 1 which the painter regarded as most important. Its subject is the execution past Mexican firing team of a Habsburg emperor who had been installed by Napoleon Iii. Neither the paintings nor a lithograph of the subject were permitted to exist shown in France.[xx] As an indictment of formalized slaughter, the paintings look back to Goya,[21] and conceptualize Picasso's Guernica.

In January 1871, Manet traveled to Oloron-Sainte-Marie in the Pyrenees. In his absenteeism his friends added his name to the "Fédération des artistes" (come across: Courbet) of the Paris Commune. Manet stayed away from Paris, possibly, until after the semaine sanglante: in a letter to Berthe Morisot at Cherbourg (10 June 1871) he writes, "We came back to Paris a few days ago..." (the semaine sanglante ended on 28 May).

The prints and drawings drove of the Museum of Fine Arts (Budapest) has a watercolour/gouache by Manet, The Barricade, depicting a summary execution of Communards past Versailles troops based on a lithograph of the execution of Maximilian. A similar slice, The Barricade (oil on plywood), is held past a private collector.

On 18 March 1871, he wrote to his (amalgamated) friend Félix Bracquemond in Paris most his visit to Bordeaux, the provisory seat of the French National Assembly of the Third French Republic where Émile Zola introduced him to the sites: "I never imagined that France could be represented by such doddering erstwhile fools, not excepting that little twit Thiers..."[22] If this could exist interpreted as support of the Commune, a following letter to Bracquemond (21 March 1871) expressed his idea more conspicuously: "But party hacks and the ambitious, the Henrys of this world post-obit on the heels of the Milliéres, the grotesque imitators of the Commune of 1793". He knew the communard Lucien Henry to have been a former painter'south model and Millière, an insurance amanuensis. "What an encouragement all these bloodthirsty caperings are for the arts! But there is at to the lowest degree one consolation in our misfortunes: that we're not politicians and have no desire to be elected equally deputies".

The public effigy Manet admired most was the republican Léon Gambetta.[23] In the oestrus of the seize mai insurrection in 1877, Manet opened upwards his atelier to a republican balloter meeting chaired by Gambetta's friend Eugène Spuller.[23]

Paris [edit]

Manet depicted many scenes of the streets of Paris in his works. The Rue Mosnier Decked with Flags depicts red, white, and blueish pennants covering buildings on either side of the street; another painting of the same title features a one-legged homo walking with crutches. Once more depicting the same street, but this time in a different context, is Rue Mosnier with Pavers, in which men repair the roadway while people and horses move past.

The Railway, widely known as The Gare Saint-Lazare, was painted in 1873. The setting is the urban landscape of Paris in the belatedly 19th century. Using his favorite model in his last painting of her, a fellow painter, Victorine Meurent, also the model for Olympia and the Luncheon on the Grass, sits before an iron contend property a sleeping puppy and an open book in her lap. Adjacent to her is a little daughter with her back to the painter, watching a railroad train pass beneath them.

Instead of choosing the traditional natural view as groundwork for an outdoor scene, Manet opts for the iron grating which "boldly stretches beyond the sail"[24] The but evidence of the railroad train is its white cloud of steam. In the distance, modern apartment buildings are seen. This arrangement compresses the foreground into a narrow focus. The traditional convention of deep infinite is ignored.

Historian Isabelle Dervaux has described the reception this painting received when it was get-go exhibited at the official Paris Salon of 1874: "Visitors and critics found its subject baffling, its composition incoherent, and its execution sketchy. Caricaturists ridiculed Manet's picture, in which only a few recognized the symbol of modernity that it has become today".[25] The painting is currently in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.[26]

Manet painted several boating subjects in 1874. Boating, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, exemplifies in its conciseness the lessons Manet learned from Japanese prints, and the abrupt cropping by the frame of the boat and sail adds to the immediacy of the image.[27]

In 1875, a book-length French edition of Edgar Allan Poe's The Raven included lithographs by Manet and translation by Mallarmé.[28]

In 1881, with pressure from his friend Antonin Proust, the French government awarded Manet the Légion d'honneur.[29]

Late works [edit]

In his mid-forties Manet's health deteriorated, and he developed astringent pain and fractional paralysis in his legs. In 1879 he began receiving hydrotherapy treatments at a spa nigh Meudon intended to meliorate what he believed was a circulatory problem, but in reality he was suffering from locomotor ataxia, a known side-effect of syphilis.[30] [31] In 1880, he painted a portrait at that place of the opera singer Émilie Ambre as Carmen. Ambre and her lover Gaston de Beauplan had an estate in Meudon and had organized the first exhibition of Manet's The Execution of Emperor Maximilian in New York in Dec 1879.[32]

In his final years Manet painted many pocket-sized-calibration still lifes of fruits and vegetables, such as A Bunch of Asparagus and The Lemon (both 1880).[33] He completed his terminal major piece of work, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère), in 1882, and it hung in the Salon that twelvemonth. Afterwards, he limited himself to small formats. His last paintings were of flowers in glass vases.[34]

Expiry [edit]

In April 1883, his left human foot was amputated because of gangrene caused by complications from syphilis and rheumatism. He died xi days subsequently on xxx April in Paris. He is buried in the Passy Cemetery in the metropolis.[35]

Legacy [edit]

Manet'south public career lasted from 1861, the year of his start participation in the Salon, until his death in 1883. His known extant works, every bit catalogued in 1975 past Denis Rouart and Daniel Wildenstein, comprise 430 oil paintings, 89 pastels, and more than 400 works on paper.[36]

The grave of Manet at Passy

Although harshly condemned by critics who decried its lack of conventional finish, Manet's piece of work had admirers from the beginning. One was Émile Zola, who wrote in 1867: "We are not accustomed to seeing such elementary and directly translations of reality. Then, as I said, there is such a surprisingly elegant awkwardness ... information technology is a truly charming experience to contemplate this luminous and serious painting which interprets nature with a gentle brutality."[37]

The roughly painted style and photographic lighting in Manet's paintings was seen as specifically modern, and as a challenge to the Renaissance works he copied or used as source material. He rejected the technique he had learned in the studio of Thomas Couture – in which a painting was synthetic using successive layers of paint on a dark-toned ground – in favor of a direct, alla prima method using opaque paint on a lite ground. Novel at the time, this method fabricated possible the completion of a painting in a single sitting. It was adopted by the Impressionists, and became the prevalent method of painting in oils for generations that followed.[38] Manet's work is considered "early mod", partially because of the opaque flatness of his surfaces, the frequent sketch-similar passages, and the blackness outlining of figures, all of which draw attention to the surface of the picture plane and the material quality of paint.

The art historian Beatrice Farwell says Manet "has been universally regarded equally the Male parent of Modernism. With Courbet he was among the showtime to take serious risks with the public whose favour he sought, the first to make alla prima painting the standard technique for oil painting and ane of the first to have liberties with Renaissance perspective and to offer "pure painting" equally a source of aesthetic pleasure. He was a pioneer, again with Courbet, in the rejection of humanistic and historical subject area-matter, and shared with Degas the establishment of modern urban life every bit acceptable material for high art."[38]

Art market [edit]

The tardily Manet painting, Le Printemps (1881), sold to the J. Paul Getty Museum for $65.1 meg, setting a new auction record for Manet, exceeding its pre-auction estimate of $25–35 meg at Christie's on 5 Nov 2014.[39] The previous auction record was held by Self-Portrait With Palette which sold for $33.2 meg at Sotheby's on 22 June 2010.[40]

Gallery [edit]

-

-

-

-

-

-

The Reading, 1865–1873

-

-

-

-

Breakfast in the Studio (the Blackness Jacket), 1868, New Pinakothek, Munich, Germany

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Still Life, Lilac Bouquet, 1883

-

Pertuiset, the lion hunter

Museu de Arte

São Paulo -

At the café, Sammlung Oskar Reinhart 'Am Römerholz', Winterthur

Come across also [edit]

- List of paintings by Édouard Manet

- Realism

- Hispagnolisme

- Portraiture

- History of painting

- Western painting

Notes [edit]

- ^ quoting Desnoyers, Fernand (1863). Le Salon des Refusés (in French). [8]

References [edit]

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Lexicon (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ Neret 2003, p. 93.

- ^ a b c d eastward Male monarch 2006.

- ^ "Édouard Manet". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Jesus Insulted by the Soldiers

- ^ The Dead Christ with Angels

- ^ King 2006, p. 20-21.

- ^ Paul Hayes Tucker, Manet's Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe, Cambridge Academy Printing, 1998, pp.12–14. ISBN 0-521-47466-3.

- ^ Rewald, John (1973) [1946]. The History of Impressionism (4th revised ed.). The Museum of Modernistic Fine art. p. 85. ISBN0-87070-369-2.

- ^ Neret 2003, p. 22.

- ^ Hunter, Dianne (1989). Seduction and theory: readings of gender, representation, and rhetoric. University of Illinois Press. p. 19. ISBN0-252-06063-vi.

- ^ Mauner & Loyrette 2000, p. 66.

- ^ Delage, R. Emmanuel Chabrier. Paris: Fayard, 1999. Chapter XI examines in item their human relationship and the effects of each other on their work.

- ^ Stevens & Nichols 2012, p. 199.

- ^ "At the Café". The Walters Art Museum.

- ^ Krell 1996, p. 83.

- ^ Krell 1996, p. 84–6.

- ^ Krell 1996, p. 87–91.

- ^ Krell 1996, p. 91.

- ^ Krell 1996, p. 89.

- ^ Wilson-Bareau, Juliet, ed. (2004). Manet past himself. UK: Little Dark-brown.

- ^ a b Nord, Philip Chiliad. (1995). The Republican Moment: Struggles for Commonwealth in Nineteenth Century France. Harvard University Press. pp. 170–171.

- ^ Gay, p. 106.[ clarification needed ]

- ^ Adams, Katherine H.; Keene, Michael 50. (2010). After the Vote Was Won: The After Achievements of Xv Suffragists. McFarland. p. 37. ISBN978-0-7864-4938-v.

- ^ "Art Object Page". Nga.gov. Archived from the original on 3 Oct 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Herbert, Robert Fifty. Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society. Yale Academy Press, 1991. p. 236. ISBN 0-300-05083-six.

- ^ "NYPL Digital Gallery | Browse Title". Digitalgallery.nypl.org. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ "Discover no. LH//1715/41". Base Léonore (in French).

- ^ Meyers, Jeffrey (2005). Impressionist Quartet: the Intimate Genius of Manet and Morisot, Degas and Cassatt. Orlando: Harcourt. p. 80. ISBN0151010765.

- ^ "Manet, Édouard" in Benezit Lexicon of Artists. Oxford Art Online (Oxford University Press), accessed 23 November 2013 (subscription required).

- ^ Tinterow, Gary; Lacambre, Geneviève (2003). Manet/Velázquez: The French Taste for Spanish Painting. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 503. ISBN9781588390400.

- ^ Mauner & Loyrette 2000, p. 96–100.

- ^ Mauner & Loyrette 2000, p. 144.

- ^ Kiroff, Blagoy (2015). Edouard Manet: 132 Master Drawings. ISBN978-6051761886.

- ^ Stevens & Nichols 2012, p. 17.

- ^ Stevens & Nichols 2012, p. 168.

- ^ a b Farwell, Beatrice. "Manet, Edouard." Grove Art Online. Oxford Fine art Online. Oxford Academy Printing. Web.

- ^ Manet Le Printemps, Lot 16, Christie'due south Impressionist & Modern Evening Sale, 5 November 2014, New York

- ^ Nakano, Craig (5 November 2014). "Getty breaks record with $65.ane-million purchase of Manet'south 'Spring'". Los Angeles Times.

Further reading [edit]

- Tedman, Gary (2012). Paris 1844, Manet and Courbet: from Aesthetics and Alienation. Naught Books. ISBN978-1-78099-301-0.

Short introductory works [edit]

- King, Ross (2006). The Judgment of Paris: The Revolutionary Decade that Gave the Earth Impressionism. New York: Waller & Visitor. ISBN0-8027-1466-8.

- Lew, Henry R. (2018). "Affiliate 10 Edouard Manet". Imaging the World. Hybrid Publishers.

- Neret, Gilles (2003). Manet. Taschen. ISBN3-8228-1949-2.

- Richardson, John (1992). Manet. Phaidon Colour Library. ISBN0-7148-2755-X.

Longer works [edit]

- Brombert, Beth Archer (1996). Édouard Manet: Insubordinate in a Apron Glaze. ISBN0-316-10947-nine. and Brombert, Beth Archer (1997). Édouard Manet: Rebel in a Frock Coat (paperback ed.). ISBN0-226-07544-iii.

- Cachin, Françoise (1983). Manet 1832-1883. ISBN0-87099-349-6.

- Cachin, Françoise (1990). Manet (in French) (1991 English language translation ed.). ISBN0-8050-1793-3.

- Cachin, Françoise (1995). Manet: Painter of Modern Life. New Horizons. ISBN0-500-30050-X.

- Clark, T.J. (1985). The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers (2000 paperback ed.). ISBN0-500-28179-3.

- de Leiris, Alain (1969). The Drawings of Édouard Manet. ISBN0-520-01547-nine.

- Friedrich, Otto (1993). Olympia: Paris in the Age of Manet. ISBN978-0671864118.

- Marlow, Tim; Grabsky, Phil; Harding, Ben; Royal Academy of Arts (2013). Manet: Portraying Life: from the Regal Academy of Arts, London. Phil Grabsky Films. OCLC 856905666.

- Krell, Alan (1996). Manet and the Painters of Contemporary Life. Thames and Hudson. p. 83.

- Stevens, Mary Anne; Nichols, Lawrence W., eds. (2012). Manet: Portraying Life. Toledo: Toledo Museum of Fine art. p. 199. ISBN9781907533532.

- Mauner, G. L.; Loyrette, H. (2000). Manet: The Nevertheless-Life Paintings. New York: H.North. Abrams in clan with the American Federation of Arts. p. 66. ISBN0-8109-4391-iii.

External links [edit]

- Works by or about Édouard Manet at Net Archive

- Marriage Listing of Artist Names, Getty Vocabularies. ULAN Full Record Display for Édouard Manet, Getty Enquiry Institute

- Impressionism: a centenary exhibition, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (p. 110–130)

- Manet, a video documentary almost his work

- Documenting the Golden Historic period: New York Metropolis Exhibitions at the Turn of the 20th Century

- The Private Collection of Edgar Degas, fabric on Manet's human relationship with Degas, Metropolitan Museum of Fine art

- Jennifer A. Thompson, "The Battle of the USS 'Kearsarge' and the CSS 'Alabama' past Edouard Manet (true cat. 1027)" in T he John M. Johnson Drove: A History and Selected Works, a Philadelphia Museum of Art gratis digital publication.

albrittonshase1964.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89douard_Manet

0 Response to "Painter Artist Begins the Transition From Realism to Impressionism in the Art World"

Publicar un comentario